In the years since I published a memoir about my husband’s sudden death and the discoveries of infidelity that followed, I’ve received emails from readers who want to be sure that my life has turned out alright. They ask about my child, who is no longer a six-year-old, but a young adult. They want to know if I’m still with the partner I met at the end of the book. Yes, I type back. I don’t tell them that he and I have lived several memoirs worth of experiences since then, because that might be too much plot. When I open my book to re-read pages readers reference, I understand that they are genuinely concerned about that woman who lived through those experiences. But I wonder if I’d even recognize her if she walked into a room.

As a writer of personal nonfiction, I worry that with every memoir or essay, I risk fragmenting and simplifying my life into words living on pages in books, magazines, or online. From my conversations with fellow writers, I know I’m not alone grappling with this dilemma, whenever a story exposes parts of our personal lives.

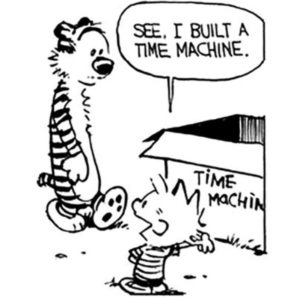

Writing memoir is time travel. It’s a bit like a Calvin and Hobbes cartoon strip, the head-trippy ones where Calvin builds a time travel machine out of a cardboard box and sends a version of himself back a few hours to do his homework. Things never turn out quite as Calvin plans, with comic results and metaphysical implications. Over two memoirs, I’ve sent a researcher self to excavate my personal life and the geopolitical past to create stories for the present. Each book marks a true point in time and space, a mark on a map. And then, my life moves forward, leaving behind a part of me as the narrator.

For readers of memoir, that self is forever fixed in printed or digitized pages, whether they encounter a book weeks, months, or years after publication. The narrator they are meeting is the woman who lived those experiences; my narrative voice is a character who lives in the present tense for those readers meeting her for the first time. Unlike Calvin’s alter egos who return to the present to deliver completed homework, the she who was me lives in the past and she’ll be there forever. The story I told remains true even, though present me has been changed by the passage of time and by the act of writing about those life-shattering events. In fact, it was the writing process that helped me leave her behind.

But what happens to the me living in the present? Am I losing parts of her?

There is an opportunity to reframe the memoir-writing endeavor as a gift to yourself and your future readers. You may have begun your book or essay to heal yourself from a traumatic experience, to unravel a secret, or to grieve a loss, but along the writing way you’ll discover something universal in your individual story that is powerful and true that you want to share. In that case, giving something honest from your life to readers doesn’t mean you will lose parts of yourself in the time machine.

Speaking of honesty. For me, the editing process is a precious time to assess my motives for writing about my personal experience. While it is essential for memoirists to push into uncomfortable emotional places, the motivation for doing so should be simple. You want to enlighten and open minds, not merely shock your readers with a crazy plot. They may open your book because chapter one promises to keep pages turning, but it is your unique and authentic voice that will keep readers with you to the end. I really do strive to write as I speak; my speaking/writing voice won’t be anything like yours. I accept that my voice will change over time as I practice my craft. As you work, take time to listen to your own way of expressing ideas. The word choices and quirks of your voice are treasures to share now—and to store in your own personal time machine.

If you craft your time machine with care, it will be sturdier than Calvin’s flimsy cardboard and will hold all the many pieces of your life that you choose to share in your writing. If you have done your best to ground your work in authenticity, you can revisit your narrator self in his/her/their time machine from time to time, to see how you’ve grown and changed. In this way your life in the present and your life from the past, turned into art, are no longer separate, but unified. Like me, you too might find that as time passes your earlier narrator self is hard to recognize, but the pages you’ve written will still reveal truth to your readers. That eternal truth is why we can pick up a memoir published a hundred years ago and still find a story that touches us in the present. And it is a good reason for you to persevere in your work today.

(All edits approved by author, Julie Metz, 7/15/2021)